Nearly one in five Amercians lives with a mental illness, and the COVID-19 pandemic has created a national mental health crisis. Most Americans with mental health concerns turn to religious leaders as their first recourse. But how do faith leaders and communities respond to them? And how has mental health in faith communities been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic?

The Mental Health in Congregations Study (MHCS) addresses these questions through a mixed-methods approach consisting of

- surveys of community members (n=3,491) and

- interviews with community leaders, including clergy and lay leaders (n=78).

Our study proceeded in three phases:

Phase 1 (2017-2019): 13 communities in TX (n=1,201)

Phase 2 (2018-2019): 6 communities in DC, MD, VA (n=681)

Phase 3 (Oct - Dec 2020): 12 communities in TX, DC, MD, VA (n=1,609)

Publications

Fitzgerald, Caitlin Anne, and Brandon Vaidyanathan. “Faith Leaders’ Views on Collaboration with Mental Health Professionals.” 2023. Community Mental Health Journal 59 (3): 477–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/

Gabriel Acevedo, Reed DeAngelis, Jordan Farrell, and Brandon Vaidyanathan. 2022. “Is it the Sermon or the Choir? Pastoral Support, Congregant Support, and Worshiper Mental Health.” Review of Religious Research 64 (4): 577–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/

Jacobi, Christopher Justin, Maria Andronicou, and Brandon Vaidyanathan. 2022. “Looking beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Congregants’ Expectations of Future Online Religious Service Attendance.” Religions 13(6): 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/

Jacobi, Christopher, Jennifer Charles, Brandon Vaidyanathan, Emma Frankham, and Bailey Haraburda. 2022. “Effects of familiarity and causal attributions on stigma towards mental illness and substance use disorders in faith communities.” Stigma & Health 7(2): 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/

Jacobi, Christopher, Richard G. Cowden, and Brandon Vaidyanathan. Association of Changes in Religiosity with Flourishing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study of Faith Communities in the U.S.” Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.

Jacobi, Christopher Justin, Maria Andronicou, and Brandon Vaidyanathan. 2022. “Mental Health Correlates of Sharing Personal Problems in Congregations during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.

Vaidyanathan, Brandon, Jennifer Charles, Tram Nguyen, and Sahara Brodsky. 2021. “Religious Leaders’ Trust in Mental Health Professionals.” Mental Health, Religion and Culture. https://doi.org/10.1080/

Frankham, Emma, Christopher Jacobi, and Brandon Vaidyanathan. 2021. “Race, trust in police, and mental illness crisis support.” Contexts (Fall 2021). https://doi.org/10.

Key Findings

Stigma and mental health literacy of faith community members

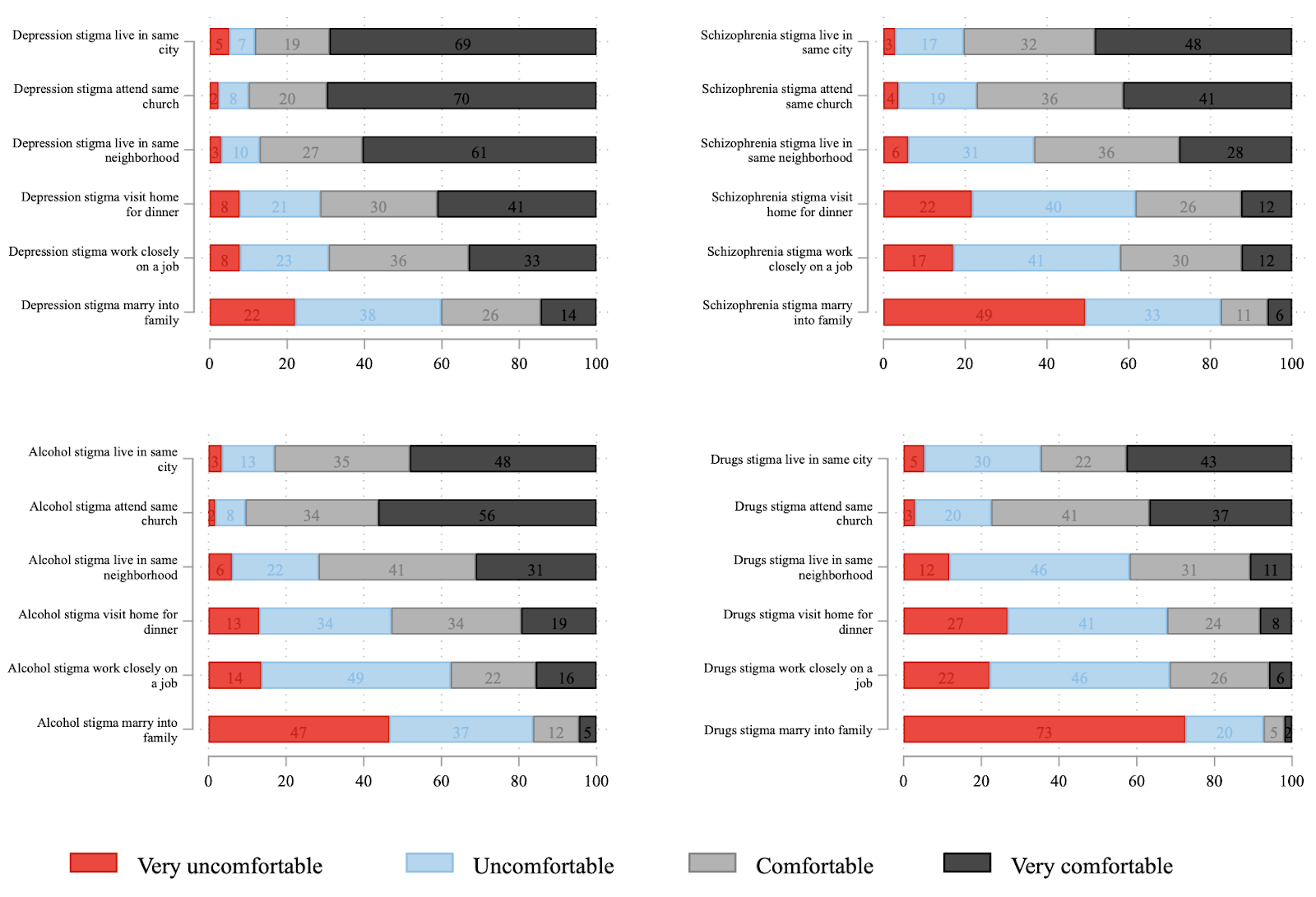

- Members of faith communities show the least stigmatizing attitudes (measured in terms of discomfort) towards persons suffering from depression, and are more stigmatizing towards schizophrenia and substance use disorders (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Stigma across different mental health and substance use disorders

- Faith community members attribute mental health challenges primarily to genetic, biochemical and situational causes, rather than spiritual causes. They thus show a relatively high level of mental health literacy, which is important for mental health professionals to recognize.

- Personal familiarity with mental health conditions is not sufficient to reduce stigma: it helps for depression but not for schizophrenia and substance use disorders.

- Those who see mental illness and substance use disorders as a result of character flaws desire the most distance from persons living from those conditions.

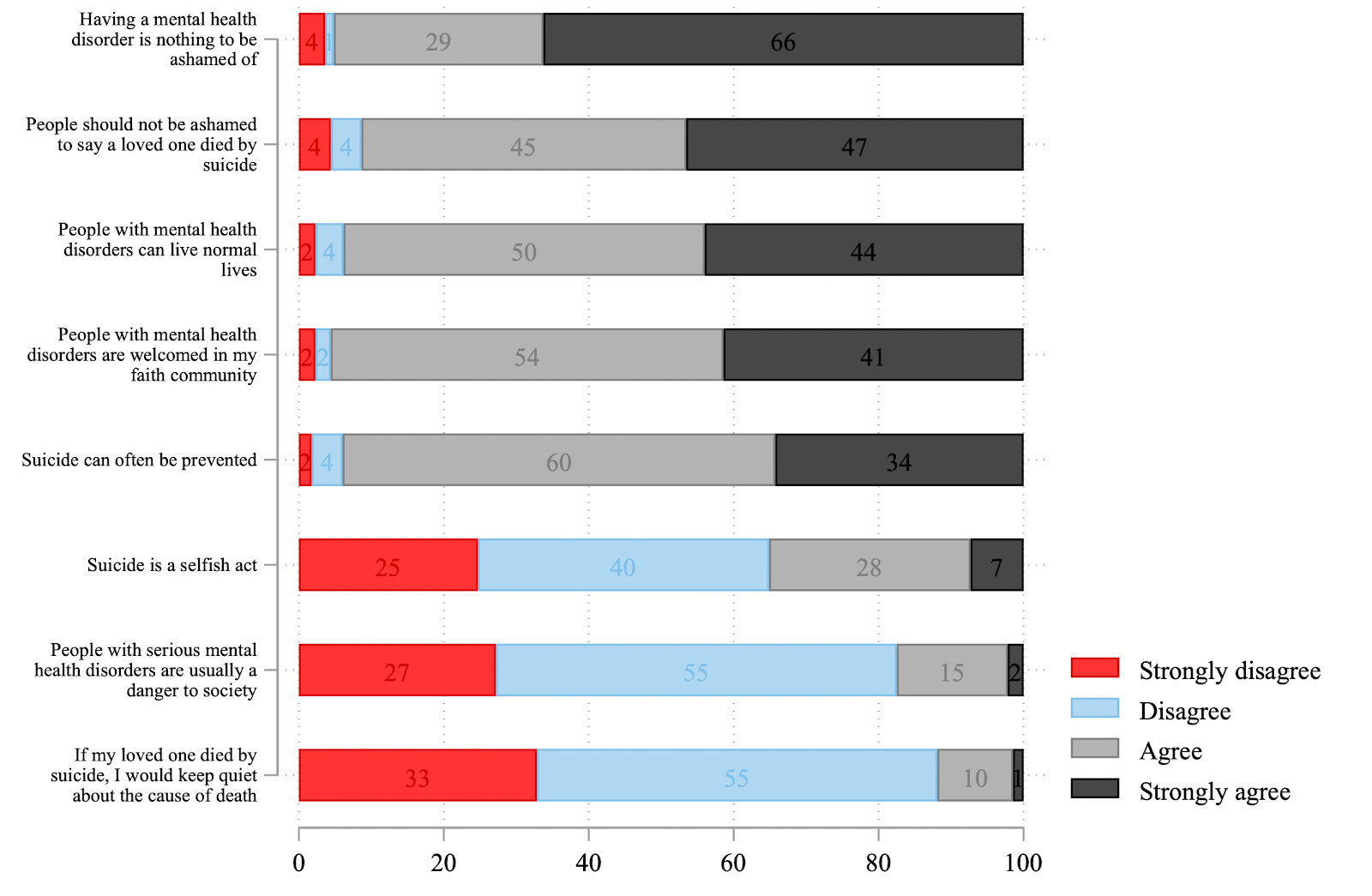

- The vast majority of participants also see mental illness and as nothing to be ashamed of and believe that people with mental health disorders are welcomed in their communities. A substantial minority sees persons with mental health disorders as dangerous, and would be hesitant to share cause of death if a loved one died by suicide (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Attitudes towards mental health disorders and suicide

Faith community leaders’ attitudes towards mental health professionals- Faith leaders adopt one of four orientations towards mental health professionals: (1) unqualified trust, (2) qualified trust (preferring either (a) therapists from their tradition, (b) those who respect their tradition, or (c) purely secular professionals), (3) distrust, and (4) dismissal as irrelevant.

- When it comes to referrals to mental health professionals, we find considerable variation in faith leaders’ practices, preferences, and resources.

- Faith leaders identify three main modes of desired collaboration with mental health professionals: (1) Education (e.g., workshops), (2) Relationship-building and dialogue; (3) Addressing external factors such as affordability of mental health care.

- When expressing stressful life events, reading scripture for insights into the future attenuates psychological distress, but only for congregants who do not believe the world is fundamentally evil and sinful. For congregants who do believe the world is evil, scripture reading amplifies the association between life events and distress.

- Support from fellow congregants is more strongly associated with better mental health outcomes than support from faith leaders; however, faith leader support amplifies the positive association between congregant support and mental health indicators.

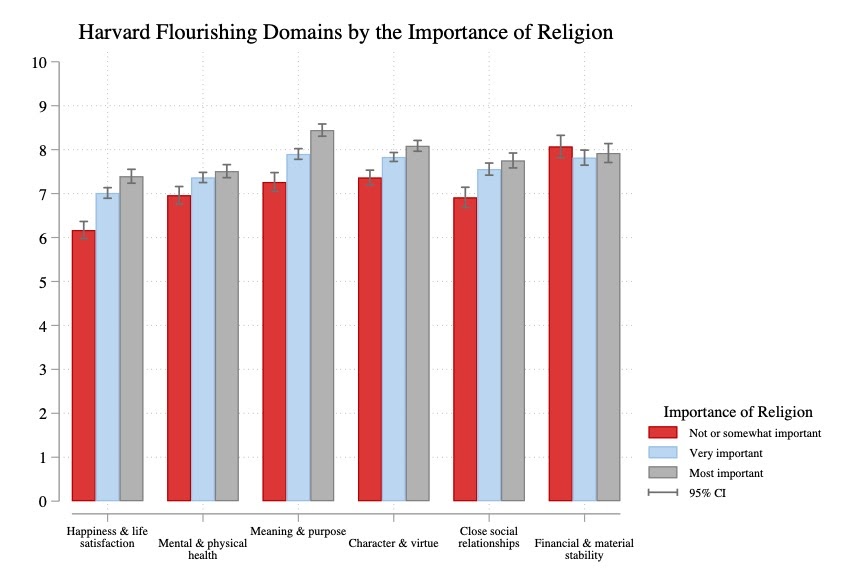

- Respondents with higher importance of faith reported better levels of well-being as measured by the Harvard Flourishing Measure (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Harvard Flourishing Measure domains by importance of religion

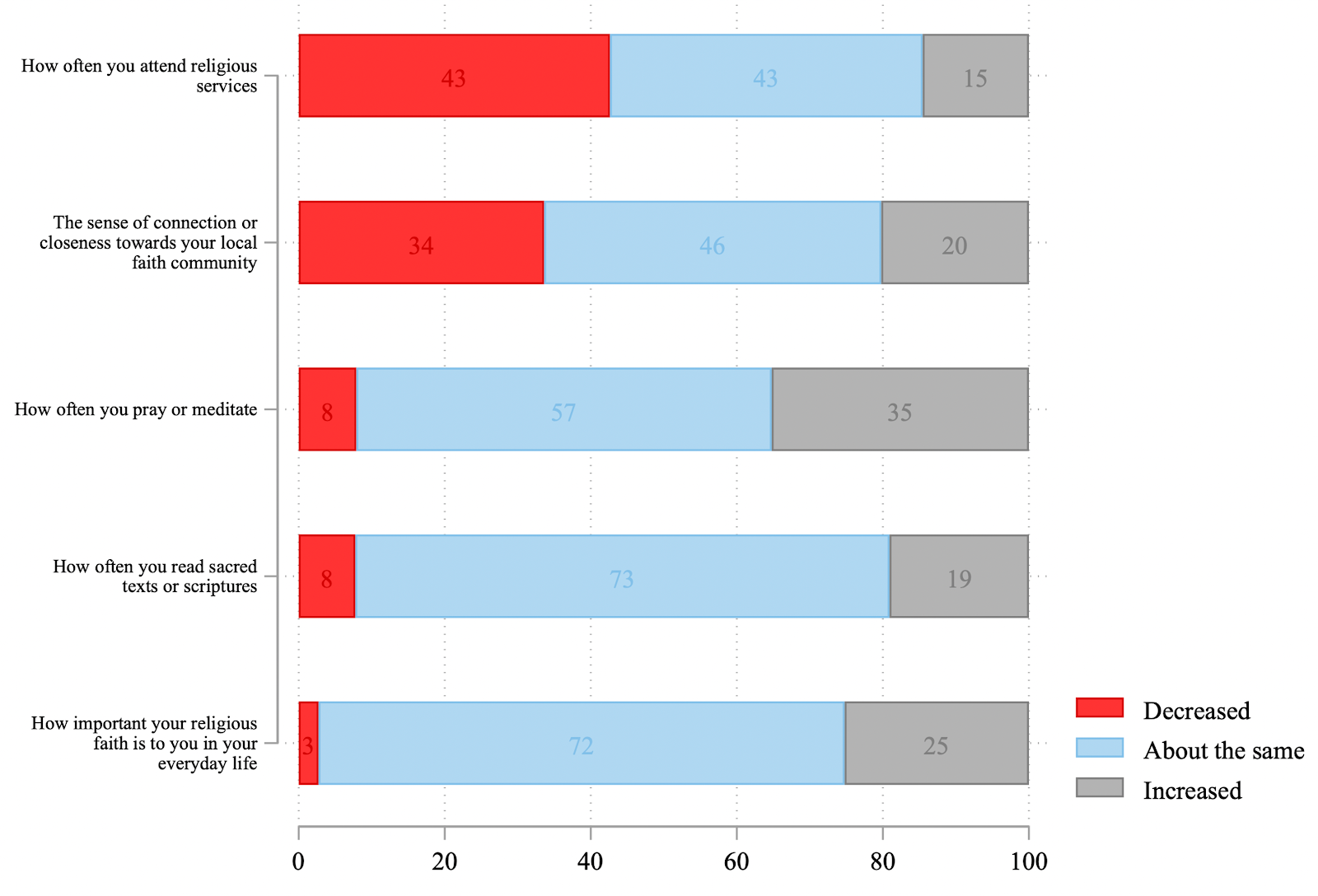

- Most active members of faith communities report no change in measures of religiosity compared to before the pandemic. More participants report increases than decreases in prayer, scripture reading, and importance of faith.

Figure 4: Changes in religiosity since the pandemic

- While attendance overall has declined due to restrictions and closures, a substantial minority of participants reports increase in attendance during the pandemic. Such attendance is primarily online, constituted by respondents who rarely attended before the pandemic; this group also tends to have lower mental health scores. They also report lower personal importance of religion, and would prefer in the future to attend a combination of in-person and online services (while participants who consider religion more important would prefer to attend in-person only). Our research suggests that the pandemic has created new modes of religious participation perhaps motivated by the anxieties of the pandemic.

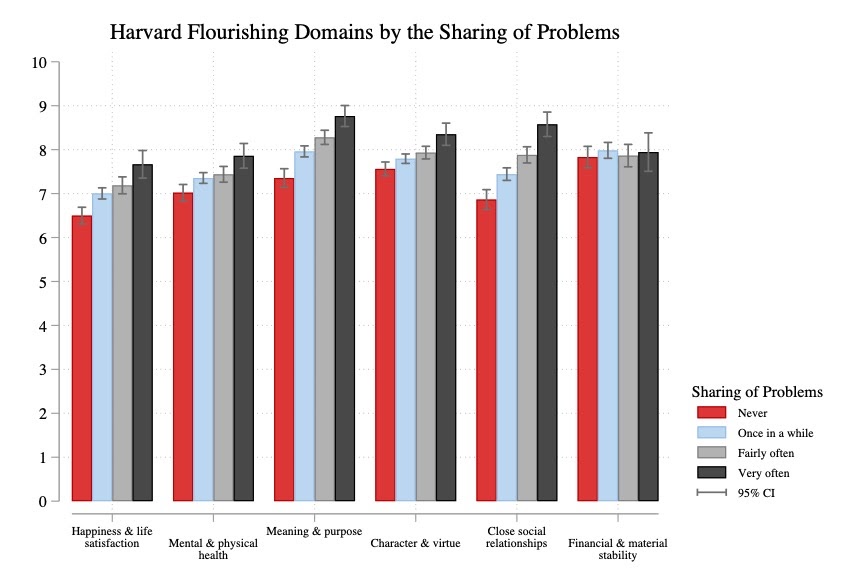

- One of the strongest factors we find associated with mental health outcomes is the frequency of sharing problems with others in the congregation. Both before and during the pandemic, we found relatively low levels of problem-sharing, with only around 30% of members sharing problems with any frequency. Individuals report better mental health outcomes in congregations with higher average frequency of problem-sharing (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Harvard Flourishing Domains by Frequency of Sharing Problems

- Members have better mental health outcomes in congregations which started mental health support groups since the pandemic and where faith leaders made themselves more accessible since the pandemic.

- COVID-19 related lockdowns, the lack of social contacts, and economic stresses are likely to exacerbate the detrimental effects of social isolation and loneliness on mental health. Our data show that respondents who feel more isolated from the people they care about or respondents who feel more lonely since the COVID-19 pandemic report significantly lower levels of well-being.

- However, religiosity plays a protective role from social isolation and loneliness. In this sense, religion can be a powerful resource to turn to during times of stress or crisis. Conversely, respondents who report a decline of religiosity since the COVID-19 pandemic have more than twice the odds of feeling isolated and lonely than respondents who did not report such a decline.

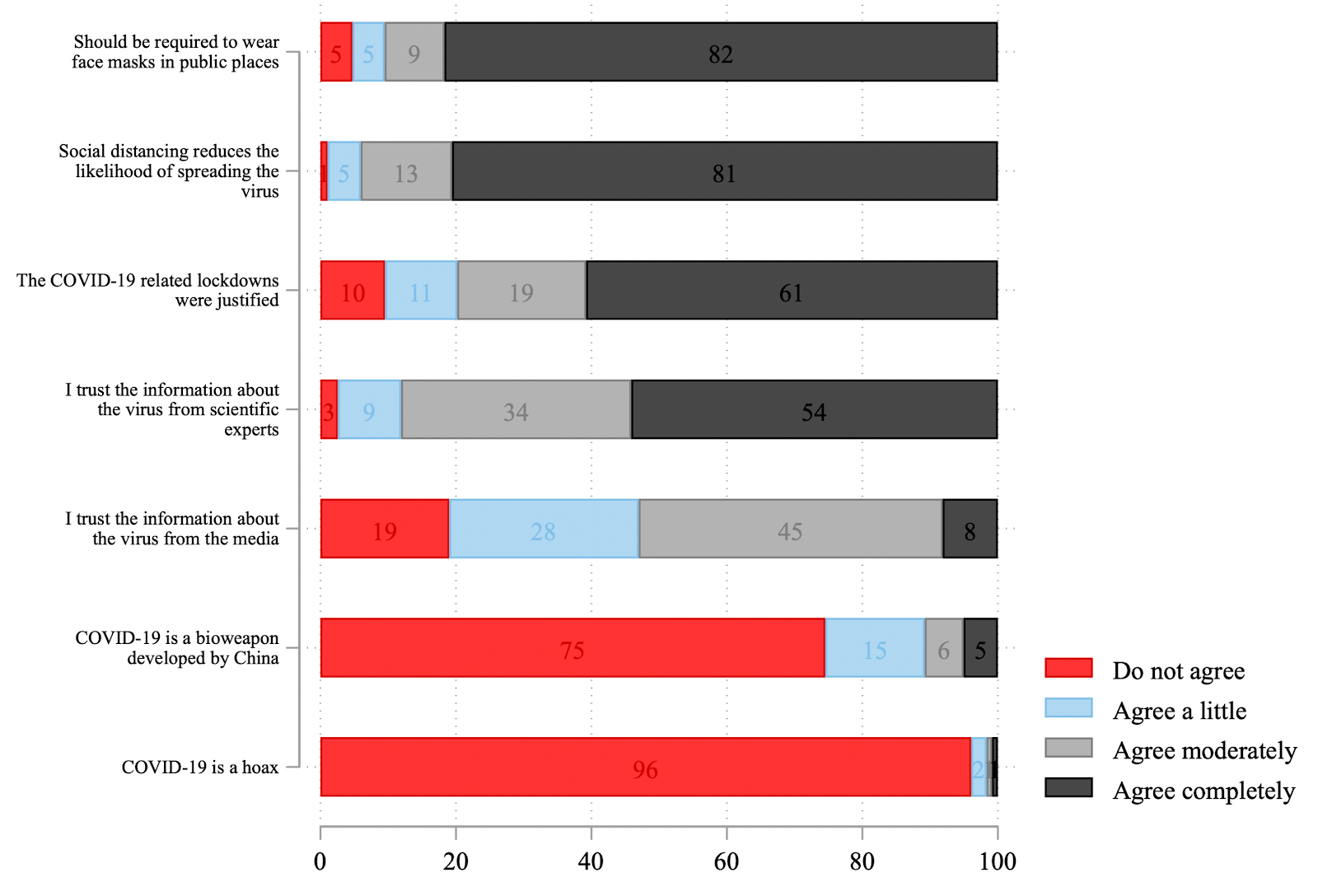

- Respondents largely agreed about the importance of masking, social distancing and the vast majority has high trust in scientists. Conspiracy theories such as “that COVID-19 is a hoax” or that it is “a bioweapon developed by China” are almost universally rejected (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Beliefs about COVID-19 and responses

- Similarly, we find overall high levels of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among respondents. However, Blacks and Hispanics are significantly more likely to express vaccine hesitancy than Whites. Other factors than had extremely strong associations with vaccine acceptance are political affiliation (Democrats being much more in favor of vaccines than Republicans or Independents), age (older respondents are more likely to favor taking the vaccine), and religiosity (the frequency of prayer is negatively associated with the willingness to take a COVID-19 vaccine).

Religious traditions represented: Participants included Christian (African American Protestant, Evangelical, Mainline Protestant, Roman Catholic, Mormon), Jewish (Reform, Orthodox), Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh Communities.*

* Buddhist, Muslim, and Sikh communities participated in leader interviews only.

Ours is not a nationally representative sample and results cannot be generalized to the national population. The samples, both before and during the pandemic, comprise predominantly female (around 65%), older (mean age of 60), educated (70-80% have at least a college degree), and long-term members of their communities (over 40% have been members in their congregation for 20 years or longer). However, faith leaders who participated in the study note that these demographics reflect the members who are regularly “in the pews,” or are the most active in their communities. So it is well-suited to inform us about patterns among urban/suburban religious populations.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the H. E. Butt Foundation and the John Templeton Foundation (#61107).